In the primordial days of this pandemic, which feel like lifetimes ago, I was sheltering in my Harlem apartment. For context, it was late February, and at the time, I was smack in the middle of a book tour for the paperback release of my memoir. Such is the way I perceive my literary life—ever what’s next? what’s next?—that I’d been prospecting when to begin drafting my next book, a novel. Once I decided to shelter in place, I also promised myself to make the most of my time at home. That promise took the form of setting out to write a novella-length prologue and obtaining a book contract for the whole novel before I moved to Chicago for a new teaching gig.

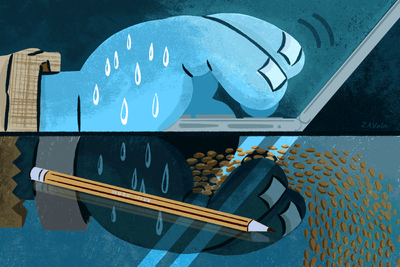

Since it was early spring, it gave me six months or so until the summer date I planned to move. Maybe you’re thinking six months is beaucoup time to draft 100 pages of manuscript, and while that might be true for some writers, for this writer—a dude who spent 13 years drafting a debut novel and seven years writing a memoir—let’s just say six months was puredee ambitious. Nonetheless, I am nothing if not an aspirant, so I set out to accomplish my goal, did it in a way that had proven effective for my previous books: marathon days of scribbling. Picture sitting at a glass-top desk facing a wall in a dim-lit office/bedroom. Imagine spending 10,11,12, sometimes 14 hours a day at said desk, brainstorming, researching, reading, writing, revising, fretting, dozing, aching, hungering, thirsting, shifting, standing, questioning, worrying…

Or in other words, I spent the first few months of the pandemic as the antithesis of what I understand as balance in work and life.

"No matter how much I’ve earned, no matter what my monetary truth is on paper, I’ve felt one foot in the poorhouse."

But let me back it up—way back. My relationship to work is a product of nurturing. The little family that could—that’s the handle I use for the single-parent family in which I was raised, one that includes my mother and two brothers. Since I was a weebit, my mother has been unemployed and collecting government assistance or underemployed and teetering on the verge of an eviction or utility shut off. While I realize much of her, and by extension, our resilient family’s, financial state was due to her struggle with addiction, those years did indeed succeed in shaping my sense of the balance between work and life: that one could be smart and assiduous and never achieve wealth, or worse, that the lot of Black folks might damn well be fiscal precarity. Count those as crucial reasons why, for all my livelong days, no matter how much I’ve earned, no matter what my monetary truth is on paper, I’ve felt one foot in the poorhouse and/or at risk of someone seizing whatever financial security I’ve accrued.

How else to stave off the possible or worse the inevitable but to work, work, work as much as I can for as long as I can? How else to beat back the incessant fear that people with the power to circumscribe how much I prosper will deem me shiftless or ungrateful or unworthy. That they will find someone else to bestow abundance on, a somebody, god forbid, who works harder or longer or with more gratitude?

Until recent, I hadn’t looked much beyond my childhood for the root of this pathology. It’s clear to me now, though, that my relationship to work has deep roots, is part of a history as old as the presence of people of African descent in this country (1619). My mother was born in the south—Alabama—as was our kinfolk dating back generations. This of course means that our relationship to work was once defined by chattel slavery, the two centuries-plus-long malevolence that coerced the labor of my forbearers from sunrise to sunset, sunup to sundown. As is well documented, that toil reaped my ancestors no personal wealth. And it should also be noted, that when they slugged out of the fields or from elsewhere on a plantation, they had to spend even more energy tending their households.

Let us not forget, either, that when the 13th amendment sanctioned the legal freedom of my people, it included a clause (Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted) which allowed for penalizing or even jailing them for deigning not to work, for the inability to find work, for loitering or idling. This is also to say that they were, despite being freedpeople on paper, second-class (or worse) citizens valuable to America—a country that touts itself as a land in which everyone has an equal shot at success—only when working, not to mention, that they were viewed as undeserving of reaping the benefits of their labor, AKA of enjoying a life outside of work.

Arithmetic those two things together—the nurturing of my mother and the historical indoctrination of untold American Blacks—and you get me: a man who was born 110 years after the Emancipation Proclamation (Aug. 16, 1975. Big up my Leos!) and who still places an inordinate value on work, too little emphasis on play or leisure; who still wonders whether I am deserving of the fruits of my labor.

And let me tell you, it’s a damn hard psychology to shake. But something happened when I hit 40 years old and realized that, lord, lord, per the CDC’s life expectancy stats, I might’ve lived half of my life. Truth be told, middle age sent me refiguring the work-life equation that had guided me from weebithood through my 30s, caused me to fathom how much of my health I’d sacrificed to imbalance, made me consider the upshot of forsaking irreplaceable hours with my children and loved ones.

Answers to those questions are at the heart of my reimagined relationship to work. And some days, lo and behold, that revisioning looks a whole lot like progress.

I’ll give you an example: after those few months of 11-, 13-, 15-hour days of working last spring, I finished a draft of my prologue and sent it to my agent. Weeks later, we sold that partial manuscript to a dream of a publisher. That publisher set the publication date to the fall of 2024, which seems both the years till kingdom come and tomorrow. At present, I live in Chicago, in an apartment with an office, where I roost at my glass-top desk facing a wall and think and read and write and angst and revise… for an hour, sometimes for 2 to 3 hours, okay, sometimes for 5 or 6 hours a day, but seldom longer than that. Do it with breaks for stretching or walking or a nap. Do it with the voice in my head growing a little more convincing—as it says, it’s okay to rest; says, hell, take a day off if you need one; says, there’s always tomorrow; as it reminds me, you’re deserving of what you’ve earned, and that includes balance.

Mitchell S. Jackson is the award-winning author of the novel The Residue Years and the critically acclaimed memoir Survival Math. He writes a column for Esquire magazine and teaches creative writing at the University of Chicago.

The one thing I’d do if I were slightly more balanced…

“Get eight hours of sleep a night. Too often, I find myself settling for 4,5,6 hours of sleep and feeling the cost of that deprivation on my energy, thinking, and creativity. When I was young, I used to joke, I’d sleep when I’m dead. And now, I feel like a lack of sleep is stealing precious time away from me.”

Florencio Zavala is a creative director, designer, artist, and founder of Estudio Zavala, a conceptual design and illustration practice addressing global needs via local actions and partnerships. Recent clients include the California Endowment, Playboy, Honda Latino, IntoAction!, and the city of LA. Zavala lives in Northeast Los Angeles with his wife and two daughters.

What’s the first visual that comes to mind when you think of balance?

Scales

Want to share this essay? Yay! Use this link.

Wellness stories you won’t find anywhere else.